Economists – assemble! This might have been the unofficial theme of the workshop on “The Economics of the DMA” hosted by the European Commission on 22-23 September 2025 in Brussels. In preparation of its DMA evaluation, the European Commission Joint Research Center (JRC) had assembled economic expertise from around the world to discuss the Regulation’s economic implications. The workshop was co-organized by the JRC (Nestor Duch-Brown), the Toulouse School of Economics (Alexandre de Cornière) and the Yale Tobin Center for Economic Policy (Fiona Scott-Morton).

By Sebastian Steinert

The agenda was packed with 18 presentations in 1,5 days and covered a wide range of topics such as self-preferencing, interoperability and app store contestability. Both empirical evidence and theoretical models were presented, offering early assessments of the DMA’s observable impact as well as its broader welfare implications. The workshop provided a rare opportunity to take stock of the Regulation’s economic underpinnings at a pivotal moment, as the Commission prepares for its formal evaluation of the DMA in 2026. Who joined the fun? Leading academics from near and far (e.g. Amelia Fletcher, Alexandre de Streel, Alissa Cooper, Julian Wright), economic consultants (e.g. from Compass Lexecon and Bruegel), and of course the Commission’s DMA enforcers, interested in getting the latest scientific insights.

Economists’ sigh of relief

Is there any room for economics in the DMA? By design, the DMA departs from the effects-based analysis, so infamous in competition law. The DMA applies “independently from the actual, potential or presumed effects of the conduct of a given gatekeeper” (Recital 11 DMA). But dear economists, worry not! Rita Wezenbeek, Director of DMA Enforcement at DG Connect (or “the administration”, as she was announced), has got your back. In her opening keynote she highlighted that economic theory is already fed into the design of the DMA obligations and that economics are essential in assessing Gatekeepers’ compliance and the effectiveness of the Regulation. The room full of economists breathed a sigh of relief.

Still, how can the Commission avoid the protracted disputes over methodology that have long characterized antitrust litigation? In response to my question from the floor, Wezenbeek explained that the DMA’s framework is a more “ring-fenced exercise,” rooted in specific provisions and free from the “pages and pages” of analysis surrounding imprecise concepts such as consumer welfare. Considering the DMA is limited to the very precise notions of contestability and fairness, I don’t expect economists to fear for their jobs.

The DMA stands its ground

RitaWezenbeek also used her opening keynote to take stock of the DMA enforcement by the Commission’s 90-strong team. Beyond the closed proceedings and ongoing investigations, the commission “very much relies on regulatory dialogue.” She also addressed criticism of the DMA, which she said, comes from both sides of the spectrum:

some say the DMA is detrimental to innovation and consumer welfare (Apple just called for an abolishment of the law). Others criticize, the DMA (enforcement) is not effective enough in creating contestable markets with investment opportunities for competitors. She dismissed both. The DMA legislator wanted to create opportunities for everyone in the EU and the DMA would already be showing the first positive effects. As examples she mentioned browser choice-screens, unbundling (e.g. Android and Gmail), less aggregation of personal data (Meta), alternative payment systems, device interoperability (Apple), real time data access and advertising information. However, “we are only two years down the road” and it will take more time to see “effective compliance”. Wezenbeek didn’t have much empathy for Big Tech’s complaints: tech giants with systemic power must assume their responsibility, and the DMA is not about penalizing scale but about ensuring fairness for European users. Crucially, she added, the EU is not acting in isolation: jurisdictions from the UK and Brazil to South Korea, Japan, Australia, and even the US are pursuing the same objectives, albeit through different instruments.

Measuring the DMA’s impact in a hot tub

After Wezenbeek’s keynote it was time to enter the proverbial hot tub: economists presenting their research and being grilled on their economic models. Whether scheduled early in the morning, right after lunch or at the closing of a long day, presenters could count on Fiona Scott Morton to find the blind spots and rigorously challenge their assumptions. The discussions also made clear that economists and lawyers have one thing in common: the number of opinions is equal to (if not greater than) the number of discussants.

It’s worth noting that several of the papers presented are not yet published, and some results remain preliminary. So, as with any hot tub conversation, take these takeaways with a grain of salt.

Eurowings flies higher while Skyscanner doesn’t take off

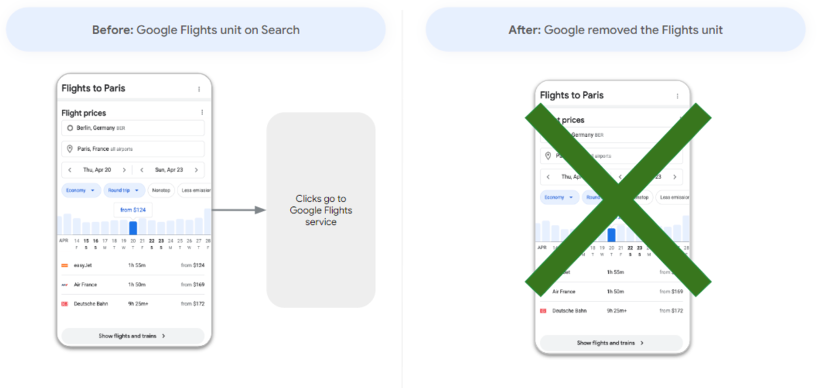

Small players in the air travel market benefit from Google Search redesign

An empirical study presented by Joan Calzada (University of Barcelona) focused on the impact of Google’s compliance with Article 6(5) DMA on the air travel market. In order to comply with the prohibition on self-preferencing in ranking, Google redesigned its Search Engine Results Page (SERP) to show offers by competing flight comparison sites as well as airlines directly on the SERP. The economists found that the redesign had a noticeable positive impact on smaller players in the air travel market. Specifically, small low-cost airlines (e.g. Eurowings) gained significant traffic (+8-13%), whereas network carriers (e.g. Lufthansa) and dominant low-cost airlines (e.g. Ryanair) did not so much. Similarly for comparison sites, smaller platforms (e.g. Gotogate) gained significant traffic (+18-20%), whereas the top 5 comparison sites (e.g. Skyscanner) didn’t see any significant effect. These results are at odds with Alphabet’s claim that the DMA-induced changes mainly benefit large intermediaries whereas direct suppliers lose out.

Google Maps keeps 90% market share

Alternative mapping services do not benefit from Alphabet’s compliance measures

The infamous Google Maps changes were discussed in a presentation by Michelangelo Rossi(Télécom ParisTech). Many end users became frustrated in 2024, when direct links to Google Maps were removed from Google Search. Google blamed the DMA for having to remove the direct link while concealing that it could also opt for a compliance mechanism allowing users to choose from multiple competing mapping service. Rossi and his colleagues assessed the impact of the removal of the Google Maps Tab on the SERP on desktop devices. They found no decrease in overall traffic to Google Maps and no increase in traffic to competitors. In fact, they observed increased search activity for the terms “maps” and “google maps”, which directed back to Google Maps. Overall, Google Maps’ market share before and after the DMA remained stable at roughly 90%. The presentation concluded that Alphabet’s compliance measures do not enhance competition, but do lead to higher search costs for users. However, they acknowledge that in the long run there could be a gradual shift to alternatives. One indication of that could be that Apple, in June 2024, has launched a web version of Apple Maps.

Amazon’s shrinking shelf

Fewer products per search, fewer sellers per product

Christian Peukert (University of Lausanne) and colleagues have scraped large amounts of data from Amazon marketplace to analyze the changes in product offerings after the implementation of the DMA and the Digital Services Act (DSA). The work is co-authored by our colleague in Düsseldorf, Reinhold Kesler (DICE). They found (preliminarily) that Amazon shows fewer products per search and that there are fewer sellers per product. They call it Amazon’s shrinking shelf. The researchers also observed Amazon’s presence in the Buy Box. Surpsingly, it went up after the DMA implementation and went down after the DSA implementation. Regarding the grain of salt in the research findings, Peukert concluded: “I showed you some data, but I don’t trust it yet”.

App Store Fees: Lessons from China

Higher app store fees reduce quantity and quality of apps

Assessing app store commission effects is tricky when Apple’s App Store and Google’s Play Store have identical fees. The situation is different in China: Play Store is not available, and a multitude of alternative app marketplaces exist on Android, either from device manufacturers (e.g. Huawei, Xiaomi) or from third parties (e.g. Tencent, Baidu). In 2014, six device manufactures established the Mobile Hardcore Cartel Alliance (MHA) and coordinated a commission increase for gaming apps from 30% to 50%. Could this be an infringement of Chinese antitrust law? At least the economists in the room couldn’t care less, they were thankful for their valuable counterfactual. Xuan Teng (University of Munich) and her colleagues studied the changes in the market for gaming apps after the commission increase. They found, that not only did fewer games enter the Android market but also the iOS market (negative spillover). This is likely driven by developers who develop games for both Android and iOS and who now face overall increased costs. Xuan Teng and colleagues also studied changes to the quality of the gaming apps. Here, they found a significant decline in new high-quality games, leading to an overall decrease in the average quality of new games. The study also reveals a widened quality gap between iOS games (higher rated) and Android games (lower rated). Overall, Xuang Teng concluded that their study not only shows that an increase in app store commission fees leads to consumer wellfare loss in the app market. But also that the impact of gatekeepers’ conduct goes beyond their own platform and beyond small suppliers.

This research adds to the debate on app store pricing under the DMA. Fiona Scott Morton and her co-authors argue in their Yale paper on this topic that DMA-Gatekeepers should not charge third-party app stores an access fee. Only narrowly defined service-related costs (e.g. for security reviews) would be permissible to remain DMA-compliant, they find.

Beyond the research presented in this blog post, the workshop included 14 further presentations that covered a variety of topics, including self-preferencing, social media regulation and interoperability. At the end of this blogpost you will find a list of all the presentations and a short description of their findings.

Future avenues of DMA application

After an intense 1,5 days, the workshop was closed by Francesca Compolongo (Director at the JRC) and Alberto Bacchiega (Director of DMA Enforcement at DG Competition).

Compolongo highlighted the importance of scientific research for DMA enforcement as “gatekeepers will react strategically to maintain their position” so that continuous monitoring and evidence-based adjustments are required. Bacchiega explained that the DMA enforcement procedures are just “the tip of the iceberg” and that a lot was achieved through informal dialogue with Gatekeepers. Regarding the future application of the DMA, he hinted to the fact that the Commission might engage more in qualitative Gatekeeper designations and there is potential to update the DMA obligations through delegated acts after a market investigation.

The workshop provided rich insights into the economics of the DMA – valuable not only for economists but also (and maybe especially) for lawyers. The Commission will publish its evaluation of the DMA in March 2026 and there is no doubt that economic analysis will play a crucial role in it. What changes might be needed to ensure contestability and fairness in digital markets in the future? If you have not read it yet, go check out SCiDA’s submission to the DMA consultation here!

If you do not want to miss any of our future blog posts, you can subscribe to the SCiDA-Newsletter here. This contribution was written by Sebastian Steinert, Maître en Droit, LL.M., who is a doctoral researcher focusing on the Digital Markets Act. His thesis is being supervised by Prof. Dr. Rupprecht Podszun.The author is grateful to the European Commission Joint Research Center, in particular Nestor Duch-Brown, for inviting him to participate.

Appendix – Overview of the other presentations at the workshop:

- Imke Reimers (Cornell University) presented that prohibitions on self-preferencing in ranking are difficult to police because of the unobservability of key metrics such as marginal costs and rank-independent quality. She recommended focusing not only on self-preferencing but also to address rankings based on variable commissions.

- Chiara Farronato (Harvard University) shared experimental data showing that a removal of Amazon brand products from the Amazon marketplace would (in the short run) decrease consumer surplus.

- Greg Taylor (Oxford University) presented a model where the provision of a marketplace is tied to ancillary services, and he analyzed the tying’s impact on sellers. He concluded that a prohibition of such tying may restore sellers’ power to compete on other factors than the price and therefore may harm consumers due to a decreased price competition.

- Miguel Risco (Bocconi University) focused on the regulation of social media platforms explaining that user sophistication influences the competitive dynamics. Therefore he argued that measures that decrease the share of naïve users are a necessary condition for improving social welfare.

- Laura Lasio (JRC) and her colleagues have studied Online Travel Agencies (OTAs) and analysed sales data from over 200 hotels in eight European countries. They found (preliminarily) that OTAs expand demand for hotels and that anti-steering policies boost hotels’ revenue while hurting their profits.

- Alexandre de Streel (University of Namur, College of Europe and CERRE) seems to have been the only lawyer to present. He explained the DMA enforcement process and shared the results from CERRE’s interviews with 21 stakeholders (DMA@1: Looking back and ahead). He recommended to have more multilateral meetings between Gatekeepers, stakeholders and the Commission, and to increase the transparency of the Commission’s enforcement priorities.

- Fabio M. Manenti (University of Padua) revisited the economic analysis of tying practices. He argued competition analysis of tying should go beyond static price effects and consider dynamic impacts on quality and innovation.

- Ananya Sen (Carnegie Mellon University) investigated the impact of a search engine having access to the market leader’s API for auto-completions/ search suggestions. Sen and colleagues found that, in the short run, removing this API access leads to a decrease in the click-through rate.

- Guillaume Thébaudin (Télécom ParisTech) presented on horizontal interoperability of platforms that are ad-funded and where users can multi-home. He shared policy implications of his research according to which interoperability may increase the market power of platforms in the ads market and mandating interoperability may not be efficient in very asymmetric markets.

- Ksenia Shakhgildyan (Bocconi University) investigated ad pricing algorithms that are offered by the same company that also runs the relevant ad auction platforms (e.g. Google Performance Max). She and her colleagues found that such platforms may have an incentive to obfuscate the data they provide to advertisers in order to increase their platform revenues. Additionally, they explain that, if advertisers were given all relevant data, they had a higher probability of winning a placement bid and the ad auction platform’s revenue would be lower.

- Alessandro Fedele (Free University of Bolzano) presented on cybersecurity risks of interoperability. He explained that interoperability can stimulate cyberattacks and that the social desirability of interoperability depends on the interplay between network externalities and the level of interoperability.

- Sandro Shelegia (University Pompeu Fabra) analysed price parity and ranking algorithms. He and his colleague modelled scenarios for different kinds of algorithms and compared their effects on welfare.

- Gastón Llanes (Catholic University of Chile) presented on app store competition. Based on the assumption that apps earn complementary revenue through ads or data, he presented a model according to which an increase in app store competition may not lead to lower store fees and even if such store fees go down they may not translate into lower app prices.

- Julian Wright (National University of Singapore) gave the final key note of the workshop, also focusing on app store contestability. Wright was retained on behalf of Epic Games as an independent expert in a litigation in Australia (Epic Games v. Apple). He argued in favor of app store contestability for lower fees, improved services and diversification of business models. According to Wright’s analysis contestability requires the prevention of foreclosure through price squeezes in fees, exclusivity, discrimination, tying/bundling and degraded experience (e.g. scare screens).