Following the European Union’s Digital Markets Act (DMA), Japan has enacted a digital competition regulation (a form of sector-specific regulation that blends competition principles with prescriptive provisions, as Lazar Radic et al. 2024 describe) with a more targeted scope in the smartphone software ecosystem: the Mobile Software Competition Act (MSCA). This blog throws some light on the MSCA’s enforcement.

by Sangyun Lee (Kyoto University)

Even before the Act’s effective date of December 18, 2025, its policy impact already seems to have begun to surface, reshaping problematic practices of Google and Apple (both designated by the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) in March 2025). For instance, it was reported in November that Apple began preparing to enable third-party app stores on its mobile operating system. Earlier, Google had announced its plans to introduce choice screens for search engines and browsers in Japan.

Sources: Tzzlala’s X post (https://x.com/Tzzlala/status/1985857946082070604) and Google’s webpage (https://www.android.com/choicescreen/msca/)

From an outcome-oriented perspective, these developments may understandably be viewed as a success. Whether the legislative intent itself was genuinely good for competition and consumer welfare is a separate question (for concerns raised about the MSCA, see here or here). But setting that question aside, in any event, the MSCA appears to be workable in delivering what it was intended to achieve.

Yet, despite these early signs of potential effectiveness of the new rule, it should be recalled that the MSCA did not emerge in a vacuum; it was introduced as a legislative response to address the ineffectiveness of Japan’s competition law, the Anti-Monopoly Act (AMA). Regardless of the MSCA’s apparent success, the underlying ineffectiveness issue remains unresolved, and strengthening competition enforcement under the AMA continues to be an essential and outstanding task for Japan.

Against this backdrop, this piece, setting the MSCA’s doctrinal details (for which, see Masako Wakui’s previous SCiDA post) aside, revisits the AMA’s under-enforcement problem that prompted Japan’s turn toward ex ante regulation, and examines its underlying causes, as well as why policymakers opted for the MSCA rather than confronting the issues directly—drawing on a comparison with Korea, a jurisdiction with broadly similar institutional features but markedly different enforcement outcomes.

Through this, it seeks to underscore the need for continued efforts to address the obstacles to stronger competition enforcement and offers several policy ideas that may be considered in pursuing this objective.

Why was the AMA regarded as ill-equipped, necessitating the MSCA?

As a starting point, it is useful to revisit the rationales that led to the MSCA’s enactment.

As in the EU, in Japan too, the ineffectiveness of the AMA (in non-cartel areas) was a key justification underpinning the need for ex ante competition regulation, with a designation system (removing the need to define relevant markets) and statutory prohibitions (removing the requirement of an analysis of anti-competitive effects).

This perception was reflected, for example, in the 2023 Market Study Report on Mobile OS and Mobile App Distribution (2023 Report) and the Regulatory Impact Assessment. In Japan’s context, the rationale was rather convincing, though not uncontroversial, considering that the formal statutes in the AMA have been significantly decoupled from the JFTC’s actual enforcement practice.

First, Article 8-4, together with Article 2(7), empowers the JFTC to order structural remedies, including break-ups, against companies in monopolistic situations; yet, this provision has never been invoked, and thus has retained only ceremonial significance.

Indeed, several points made in the 2023 Report, in my view, suggest to a large extent that the smartphone ecosystem may constitute a close example of the “monopolistic situation” within the meaning of Article 2(7), yet the JFTC did not even appear to consider attempting to rely on this provision. Perhaps this was due to a prevailing perception that the provision is not practically usable, despite calls by some academics for its modernization and meaningful application (see Wakui, 2021). At the policy document level, the potential role of Article 8-4 was last meaningfully discussed in the 2017 Report of Study Group on Data and Competition Policy (by the Competition Policy Research Center) as a means to address the data concentration issue (see its English version, pp. 25-26). Since then, the provision has received virtually no further attention in policy documents.

Second, consider the enforcement record of Article 3, which prohibits (private) monopolization. Article 3, the Japanese equivalent of Section 2 of the Sherman Act or Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), has also shown clear limitation in enforcement.

For instance, since the introduction of the surcharge (fine) system for exclusionary private monopolization by the 2009 AMA amendment (effective 2010) (see e.g., Article 7-9(2), AMA), the JFTC has imposed a fine in only one private monopolization case, the Mainami case (concerning a dominant aviation fuel supplier’s exclusive dealing). Even before that, only a very small number of exclusionary monopolization cases, such as NTT East (Supreme Court 2010) and JASRAC (Supreme Court 2015), resulted in formal sanctions (see Simon Vande Walle 2025, pp. 8-11).

Third, take the unfair trading practice (UTP) rule under Article 19 of the AMA.

For international readers unfamiliar with Japan’s system, a brief clarification may be helpful: Roughly speaking, the UTP rule, which similarly exists in competition laws of Korea and Taiwan, can be described as a Japanese equivalent to the unfair methods of competition clause under Section 5 of the US FTC Act, though only under its most expansive and progressive interpretations. The UTP prohibition enables earlier and less demanding intervention against incipient violations of the AMA by non-dominant firms—including practices that lessen competition, abuse of superior bargaining position, and unfair competition practices (see Wakui 2018, pp. 141-142 for a quick overview; see also Kawahama et al. 2008 for deeper analysis).

Source: Sangyun Lee, ‘Japan and Korea’s Competition Law – Digital Platform Cases –’ (Kyushu University, June 2025), p. 3.

As Steven Van Uytsel and Yoshiteru Uemura (2021) point out, by relying on this tool, the JFTC can sanction abuses without dominance more broadly, particularly in the digital context, without being required to conduct full-scale, precise analyses of anticompetitive effects. And in practice, the JFTC’s enforcement has been somewhat active under the UTP framework. In digital sectors particularly, it has been reported that the JFTC has handled more than 10 cases since the mid-2010s. And notably, as I have discussed elsewhere, in April 2025 the JFTC sanctioned Google under the UTP framework (for its MADAs and RSAs). This Google case marks the JFTC’s first formal sanction against a Big Tech company in Japan (albeit without a fine).

Here, one might reasonably ask why Japan needed the MSCA, given that the UTP law already appeared to be addressing the ineffective enforcement under Article 3.

This argument is reasonable, on paper. But a closer examination reveals that the UTP framework has also shown limitations in practice. As Vande Walle’s (2023) research summarises well, covering the period from 2013 to 2022, almost all digital cases in Japan were closed with commitments, or voluntary measures, without any finding of breaches of the AMA. This includes the case concerning Apple’s anti-steering, which the JFTC closed without finding any breaches, accepting only voluntary measures from Apple in 2021. Such a light-touch approach has weakened the law’s deterrent effect and effectively removed the possibility of follow-up damage claims under Articles 25-26.

That said, one may still argue that the commitments and voluntary measures have enabled the swift correction of competition concerns, especially in fast-moving digital markets, and thus cannot be regarded as evidence of ineffectiveness or under-enforcement.

That argument is not without merit. Swift resolutions can indeed play a constructive role in fast-moving digital markets. But the argument holds only when such measures operate against a credible baseline of deterrence, with appropriate sanctions serving as the rule rather than the exception. The AMA’s enforcement does not fit this description.

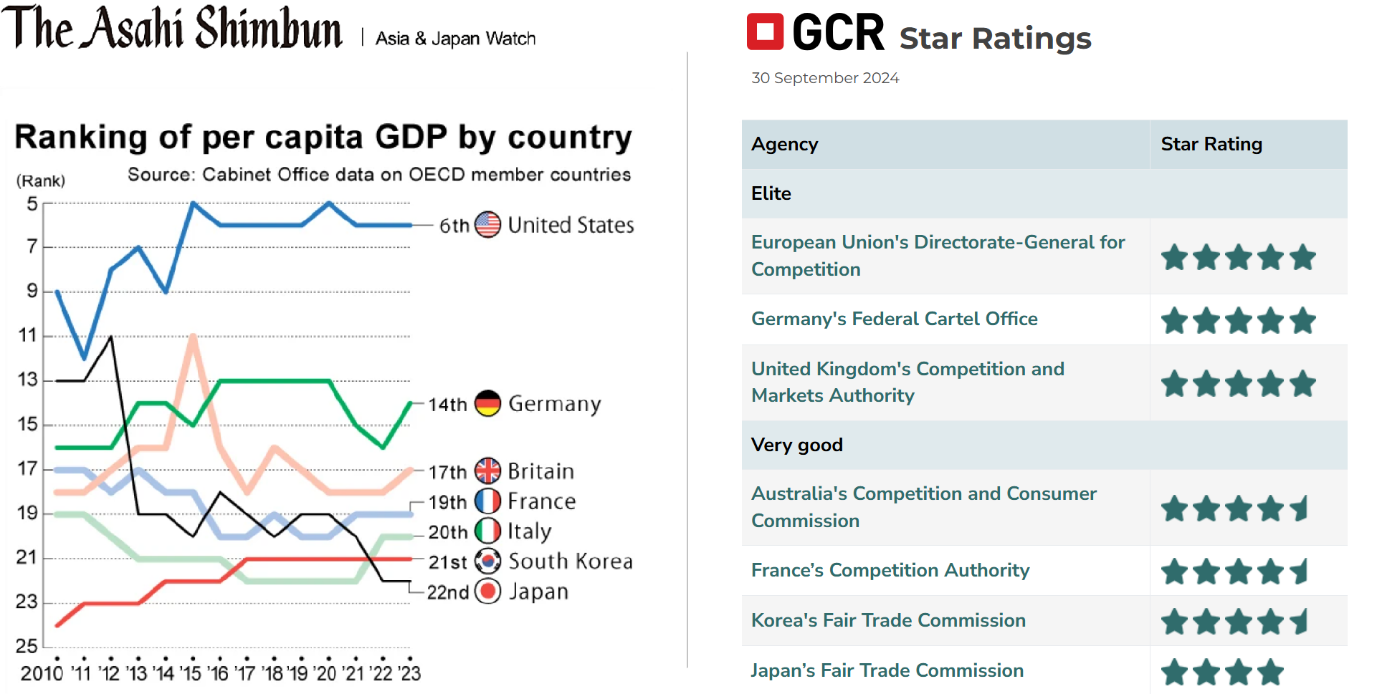

Perhaps most tellingly, the picture of Japan’s under-enforcement becomes clear, particularly when viewed in comparison with Korea, an economy of a comparable developmental stage and institutional design, where the Korea Fair Trade Commission (KFTC) operates with broadly similar institutional capacity to the JFTC and where a similar UTP framework is enshrined in the competition law, the Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act (MRFTA).

Sources: Hisashi Naito, ‘Japan’s per capita GDP ranks 22nd in OECD, behind South Korea’ The Asahi Shimbun (December 24, 2024); Global Competition Review, Rating Enforcement: Star Ratings 2024 (September 2024).

Reportedly, during a broadly similar period in which the JFTC had imposed no formal sanctions, the KFTC handled 15 infringement cases against digital platform companies, including both abuse of dominance (Article 5, formerly Article 3-2, MRFTA) and UTP (Article 45, formerly Article 23, MRFTA) cases. For illustration, the cases include the Google Play Store case, where a corrective order together with a fine of KRW 42.1 billion (approx. JPY 4.2 billion) was imposed, and the Google Android case, where a corrective order together with a fine of approximately KRW 207.4 billion (approx. JPY 20.7 billion) was imposed. (KRW 1,000 ≈ JPY 100.) It is also notable that several of the above cases have even been referred to the prosecution for criminal sanctions, and that there are several more cases where the KFTC closed without formal sanctions.

Meanwhile, although it is not a digital platform case, the 2016 Qualcomm II case is also worth noting for comparison. At times, the JFTC’s under-enforcement is attributed to the practical difficulty of imposing substantial fines on foreign firms (see Hiroshi Nakazato’s comment) and to the complexity of handling technically sophisticated cases. Yet in Qualcomm II, the KFTC imposed an exceptionally large fine, KRW 1.03 trillion (approx. JPY 103 billion), in a highly technical SEP-licensing dispute. This example illustrates that, despite such challenges, smaller competition authorities (than the European Commission or the US Federal Trade Commission, FTC) can also pursue technically complex and high-stakes cases and impose substantial financial penalties.

Taken together, I find that Japan’s digital and tech market enforcement record, where too many violations are allowed to remain unpunished to the detriment of the public interest, can reasonably be described as under-enforcement. This is all the more so given that Japan’s economy is more than twice the size of Korea’s. And this finding aligns with the rationales advanced for the enactment of the MSCA.

If the AMA has been ineffective, why?

Then, why has the enforcement of the AMA encountered such serious difficulties? And, more importantly, why were the underlying challenges or problems, if any, addressed not through broader institutional reform efforts but instead through the enactment of a narrowly targeted competition regulation, the MSCA?

Based on discussions and comments from colleagues over the past few years, I have come to view the issue along two broad dimensions (albeit tentatively).

Judicial passivity as a doctrinal constraint

First, judicial passivity can be identified as a cause, and I find that it may have been regarded as one that is difficult to resolve within any foreseeable timeframe.

Although it is nothing new, in Japan too, there is a widely shared concern about the courts’ extremely cautious approach toward competition law enforcement. In fact, the 2023 Report’s findings, including the view that the AMA enforcement alone is not sufficient to ensure timely intervention, are closely connected to this concern about judicial passivity. And apparently, this concern also formed part of the basis for the JFTC’s choice to rely on a UTP provision (specifically, one on “trading on restrictive terms”), not on monopolization, in the 2025 Google case (see commentators’ observations, which align with my view, here).

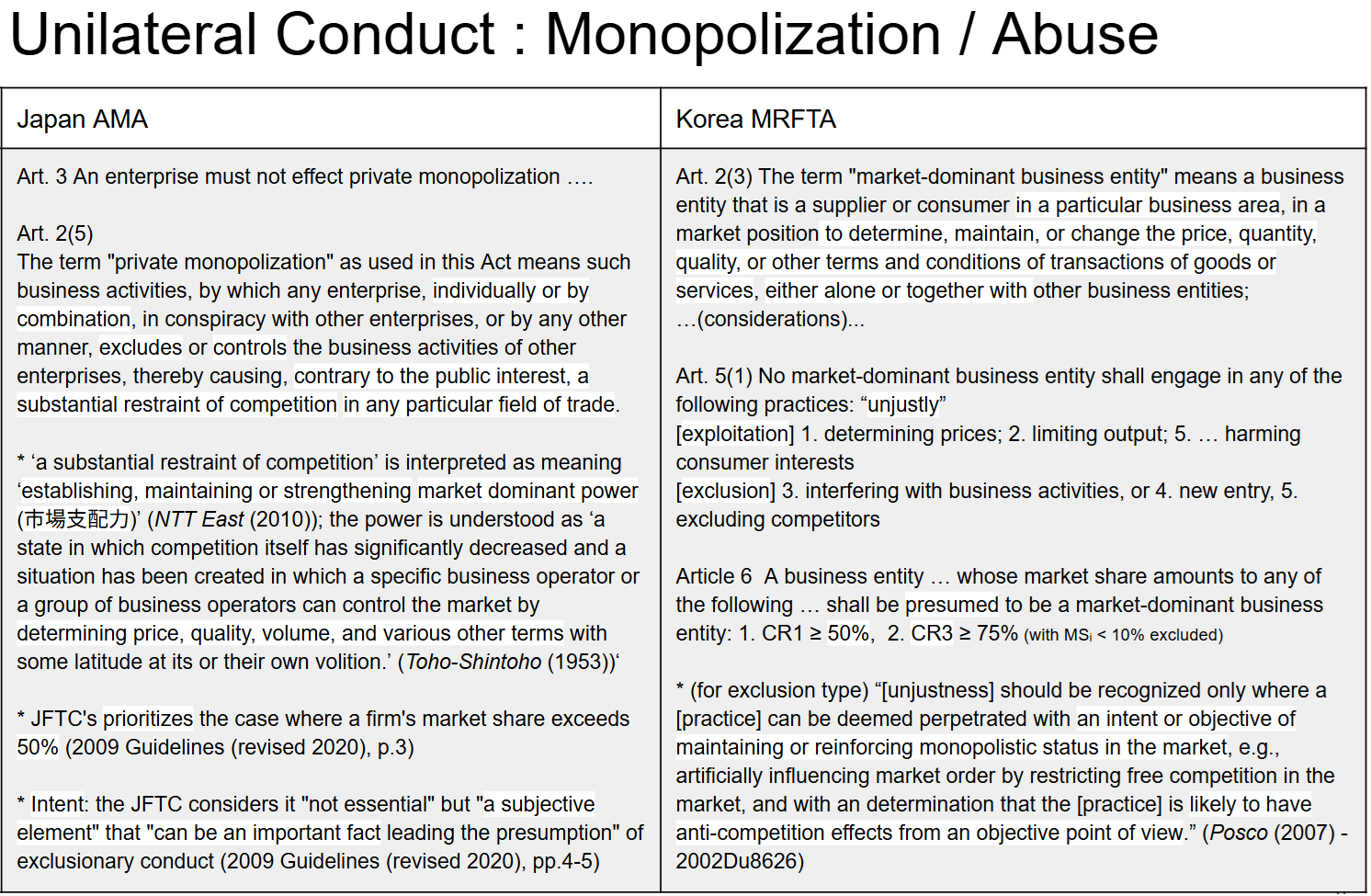

Then let us examine how Japanese courts doctrinally approach unilateral anticompetitive conduct under the AMA. What follows focuses solely on monopolization, given that the analytical framework for UTP cases (mainly, UTPs that lessen competition) can broadly be seen as a more relaxed variation of the monopolization standard.

To my understanding, when interpreting monopolization and assessing market power, the Japanese courts appear to follow an approach closer to the U.S. antitrust concept of monopoly power, as defined in du Pont (1956), drawing on the classical, Stiglerian notion of price-controlling power, rather than the exclusionary Bainian market power. It is understood as narrower and stricter than the dominance threshold of the EU.

For example, in NTT East (2010) (a vertically integrated network operator’s margin squeeze case), the Supreme Court ruled that, for exclusionary conduct to constitute monopolization under Article 3 (together with Article 2(5)), it must “artificially deviate from the scope of the normal method of competition from the point of view of forming, maintaining, or strengthening its market power.” As for the meaning of the market power, although there has been no further definitive clarification, the Tokyo High Court in the old Toho-shintoho case (1953) treated it as equivalent to one’s ability to determine price, quality, volume, and various other terms.

As elsewhere, in Japan as well, the mere possession of such power is not sufficient to violate the AMA. The power must be exercised in a manner that deviates from competition on the merits (in an “abnormal”, “artificial” way), resulting in exclusionary effects. Although the actual exit of competitors is not required to establish illegal exclusion, “forming, maintaining, or strengthening its market power” must be proved to establish the “substantial restraint of competition” requirement in Article 2(6), AMA (see Wakui (2018), p.66; Koki Arai (2019), Chapter 2).

They are certainly not very lenient. It is understandable that these judicial constraints may have contributed to enforcement difficulties, and that they were viewed as unlikely to be resolved in the short term.

JFTC’s passivity as an aggravating factor

As noted above, however, judicial passivity is hardly unique to Japan; it is a familiar issue of competition law across jurisdictions. Moreover, although Japan’s doctrinal standards are not especially low, they also do not appear aberrantly stringent when assessed from an external comparative perspective (a view that contrasts with the mainstream domestic understanding). The ‘judicial passivity’ argument alone does not seem sufficient to explain the degree of under-enforcement observed in Japan, particularly when contrasted with comparable jurisdictions, and this seems to call for a closer examination of factors internal to the JFTC.

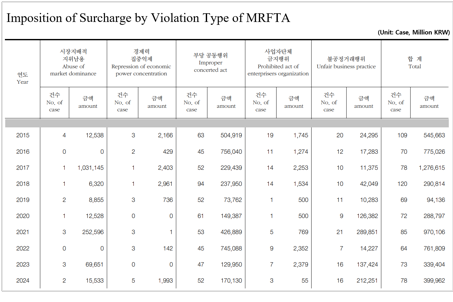

Once again, a comparison with Korea may be instructive. The Korean Supreme Court also requires a similarly demanding set of requirements to establish abuse, including the market dominant power, conduct, its anticompetitive effects, causality, and even subjective intent, since the 2007 POSCO decision (a vertically integrated steelmaker’s refusal-to-deal case). This stance has been repeatedly reaffirmed in the following cases, including the 2025 NAVER Shopping case (a dominant search platform’s self-preferencing case). Nevertheless, as seen above (and in the table below as well), the KFTC, differently from the JFTC, persistently brings MRFTA infringement cases and repeatedly tests doctrinal boundaries, despite the risk of losing on appeal and, more interestingly, academic criticisms of its over-enforcement. What, then, explains this divergence?

Source: KFTC, Statistical Yearbook of 2024 (2025), p. 32.

In my view, beyond the statutory hurdles and judicial passivity, the JFTC’s own risk-averse attitude has been a key underlying cause of the AMA’s under-enforcement and helps explain the policy choice to adopt a new rule rather than testing the AMA’s reach through enforcement. Indeed, as I discussed elsewhere, in Japan there is a perception that the JFTC tends to use its enforcement discretion not to flex its power through sanctions (as in most jurisdictions), but in the opposite way: to close cases by resolving concerns rapidly and smoothly, in order to avoid legal disputes. In this sense, the MSCA tends to be justified as a baseline that restricts the JFTC’s downward discretion.

What explains the JFTC’s risk-averse approach? While a robust account of why the agency becomes so self-restrained would require more extensive empirical research, several hypothetical propositions may nonetheless help frame the discussion.

i. From the perspective of individual enforcers’ incentives

First, if one applies a methodological individualism lens, the situation may be viewed as stemming from a lack of incentives for individual JFTC officials to take on major antitrust cases and risk losing on appeal.

In the case of the KFTC, it is observable that officials who handle significant cases, particularly those resulting in infringement findings and substantial fines, are internally praised and gain high reputations, which may contribute to their career advancement. For example, in the Qualcomm II case and the recent NAVER Shopping case (as well as other related NAVER cases handled by the agency’s ICT Task Force), the enforcers were reported (e.g., here and here) to have been selected as KFTC Employees of the Year and subsequently promoted (though, of course, case handling was not the sole factor in their advancement). Such an environment likely contributes to creating strong incentives for KFTC officials to pursue big antitrust cases.

Of course, the relevant incentives may not be purely institutional but also societal and cultural. For instance, although in Korea the NAVER decisions, Shopping (2023Du32709) and Video (2023Du38219), were later overturned by the Supreme Court, there has been little public criticism of the agency’s alleged overreach or over-enforcement (setting aside expert and academic criticisms). Rather, politicians and civil society groups tend to vocally blame the Court’s conservative stance, aligning themselves with the KFTC. Under such conditions, it is understandable that individual KFTC officials develop even stronger incentives to pursue major antitrust cases, boldly taking risks.

Meanwhile, I personally have not observed such incentive structures in Japan. There might be internal mechanisms rewarding tough and active enforcers, but they are not publicly quite visible. Also, it seems unlikely that civil society groups in Japan are as pro-competition or as vocal on economic matters as those in Korea.

Although these perceptions are tentative and provisional, if one assumes they are accurate, it can reasonably be concluded that, under such institutional and societal settings, JFTC officials have had limited incentives to pursue big monopolization cases.

ii. From the perspective of organizational design

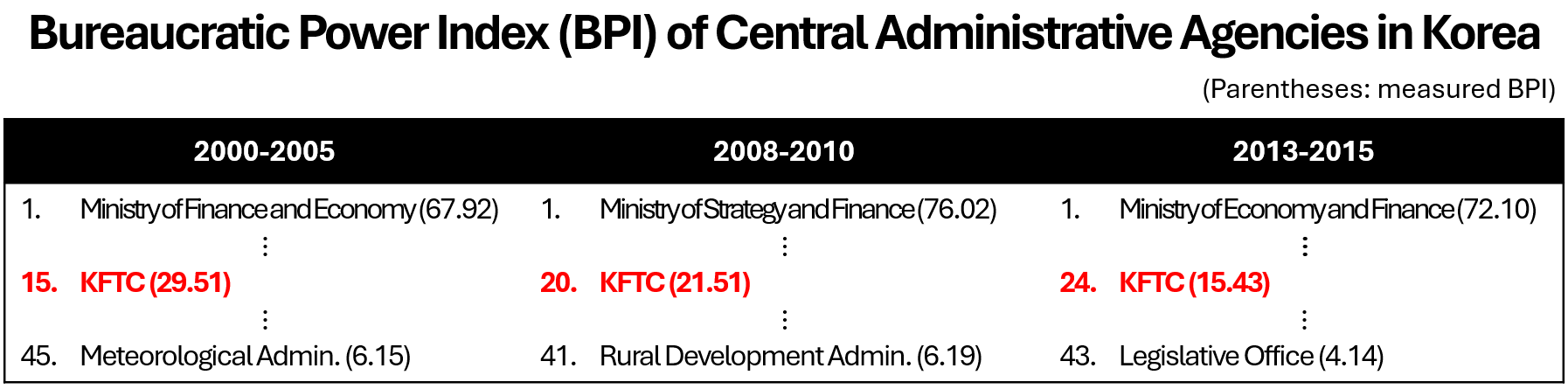

Second, the JFTC’s possibly limited bureaucratic power within the broader government may be relevant to the agency’s extreme cautiousness.

Although it is often overlooked in mainstream discourse in competition law (perhaps overshadowed by the appealing, but unrealistic, notion of “independence”), the degree of influence that competition authorities hold within the government’s overall decision-making process is very important. I find that it is perhaps more crucial than any statutory settings, particularly in East Asian contexts, where the central government, whether democratic or not, typically maintains a very strong grip over the economy.

From a comparative perspective, in Korea, the problem of a lack of bureaucratic power relative to other departments was starkly revealed in the Korean Air/Asiana Airlines merger case. This was a case in which the Korean government pursued a monopolistic deal (two-to-one deal) in the aviation sector based solely on industrial policy considerations, seriously marginalizing competition law concerns and the KFTC’s role. Putting all details aside, this case showed how the voice of a powerful competition authority, like the KFTC, can be so powerless when confronted by government departments with greater bureaucratic power, such as the Ministry of Economy and Finance.

I have not found empirical studies that quantify bureaucratic power rankings within the Japanese government, in contrast to Kenneth J. Meier’s empirical analyses of power hierarchies among US federal agencies (1980) and Jae-Rok Oh’s studies of the Korean bureaucracy, which show that the KFTC occupies a mid-level position within the Korean government (2006; 2011; and 2018). Therefore, it is difficult to assert that the JFTC’s possibly limited internal power has directly shaped its passivity.

Nevertheless, given that Japan, like Korea, has also long relied on government-led economic growth rather than competition-driven innovation, it is reasonable to suspect that internal power dynamics, operating to the disadvantage of the JFTC, the competition authority, may also shape the JFTC’s enforcement passivity by amplifying the perceived risks of losing appeals and thereby leaving the agency’s officials with little incentive to take bold actions, confronting the courts’ conservative stance.

This table has been rewritten with reference to the research results from Oh (2006), pp. 190-191, Oh (2011), pp. 83-83, and Oh (2018), p. 158. The year indicated in the top row represents the period during which each study was conducted (the period of data collection and analysis). The number before the agency’s name represents its rank, and the number in parentheses next to the agency’s name represents the measured power index.

Charting a Path Forward for Stronger AMA Enforcement

The foregoing analysis shows that none of these challenges is in any way straightforward. Against this backdrop, it is understandable that the pursuit of the MSCA may have appeared to policymakers in Japan as one of the few strategically feasible options, particularly given the wider regulatory climate of the 2020s.

That said, as noted above, it should not be forgotten that the MSCA is an exceptional and highly targeted regulatory instrument designed only to complement the AMA. At best, it functions as a symptomatic remedy that may carry significant side effects if relied upon too heavily, such as raising barriers by creating substantial compliance costs or dampening firms’ incentives to innovate, as Gail Slater has aptly pointed out. The fundamental cure for creating a robust competitive environment lies, however difficult and time-consuming it may be, in improving enforcement under the AMA.

In this light, several tentative ideas may be put forward as preliminary starting points for strengthening AMA enforcement.

First, from a substantive law perspective, a statutory presumption of market power could be considered in Japan’s context.

Currently, as Wakui (2021) notes, the JFTC rarely applies Article 3 to a firm with a market share below approximately 80%, even though its Guidelines indicate that around a 50% market share can be the point at which the agency begins to prioritise monopolization cases. In my view, while the 80% threshold (reminiscent of the notion of “superdominant position” of the European General Court in the Google Shopping case) may be reasonable for easing the burden of demonstrating effects, it is far too stringent to be a mere indication of the existence of market power.

Meanwhile, in Korea, under Article 6 of the MRFTA (formerly Article 4), dominance is statutorily presumed when a single firm’s market share exceeds 50% or three firms’ combined share exceeds 75% (excluding firms with a share below 10%). If similar presumptions were introduced in Japan, such a reform would allow the currently self-restrained JFTC to take bolder actions in future cases, much as the KFTC does.

Revising the AMA will certainly not be easy. And given that the statute (Article 2(5), AMA) explicitly refers to “monopoly”, not dominance, the introduction of a statutory presumption may well be criticised as a doctrinal shift, beyond a mere amendment.

Yet, it is notable first that, when the focus is placed on the substance of monopoly, market power, a 50% benchmark is hardly radical; it is firmly established in other jurisdictions, such as the EU (AKZO, para 60).

Additionally, the 50% quantitative threshold is already embedded in Article 2(7)(i) of the AMA as a statutory indicator of a monopolistic situation, which, as noted above, may trigger structural measures, e.g. break-ups. Admittedly, in this context, the 50% figure refers not to a share “in any particular field of trade” (a relevant market) but to a broader “share of a field of business” (a relevant industry). Even so, this statutory use of a quantitative threshold suggests that incorporating a similar quantitative indicator for market power would not be conceptually inconsistent with the existing framework of the AMA, nor would it constitute an overly radical departure from its doctrinal structure.

Source: Sangyun Lee, ‘Japan and Korea’s Competition Law – Digital Platform Cases –’ (Kyushu University, June 2025), p. 7.

Second, to encourage the JFTC to bring more monopolization cases, it may be worth considering whether the agency could be permitted to invoke Article 3 (monopolization) and Article 19 (UTP) concurrently when challenging anti-competitive unilateral conduct.

The precise historical or legal rationale behind Japan’s current approach remains unclear to me; however, unlike the KFTC, which, much like the U.S. FTC, can simultaneously rely on both abuse-of-dominance and unfair-practices provisions, the JFTC typically proceeds under either the monopolization rule or the UTP rule, but not both. From a procedural perspective, there may be room for improvement. If concurrent invocation were made possible, the agency could pursue monopolization cases with a lower degree of litigation risk, thereby facilitating more active enforcement.

Third, as discussed above, the JFTC’s risk-averse attitude, beyond the statutory hurdles or judicial passivity, may have influenced the policy choice to adopt a new rule instead of testing the AMA’s reach. In this sense, if possible, internal incentives for individual enforcers could be explored and would still merit consideration.

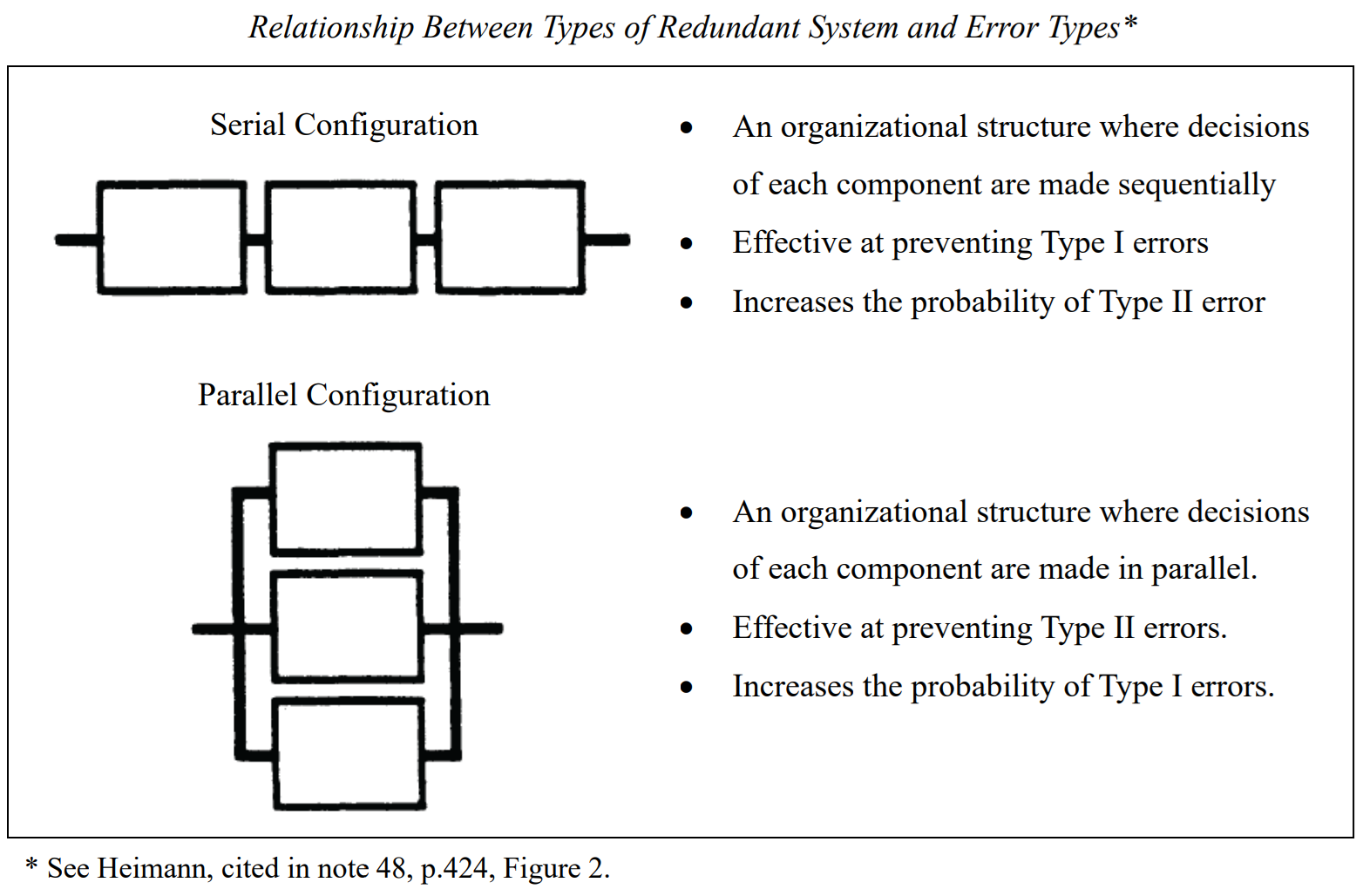

More fundamentally, from an organizational design perspective, it may also be worth rethinking whether the AMA enforcement power should necessarily be exclusive to the JFTC. As William E. Kovacic and David A. Hyman’s work (2012) shows, it is neither impossible nor unprecedented to establish multiple enforcement agencies at the same level of government or to give the power to agencies at multiple levels of government. In fact, in the view of the redundancy theory, institutional overlaps under certain conditions can help prevent erroneous omissions, that is, under-enforcement of competition law (see my paper on the theory of redundancy, 2024). For instance, beyond establishing an enforcement body that would operate entirely in parallel, installing a ministerial body for monitoring and/or enforcement of the UTPs, such as the French DGCCRF, or relaxing the filtering role of the referral requirement for criminal enforcement, as Korea has done, could also be considered.

Source: Lee, Sangyun, ‘Duplicate Powers in the Criminal Referral Process and the Overlapping Enforcement of the Competition and Criminal Authorities in Korea: An Analysis Through the Lens of the Redundancy Theory’ (October 30, 2024). ASCOLA Asia Annual Regional Workshop 2024, p.11.

Despite the precedents and theoretical grounds, one may still be sceptical about multiplicity. For such readers, it is worth noting that the effectiveness of overlapping powers in promoting enforcement outcomes has been illustrated in U.S. antitrust history. For instance, Richard S. Higgins et al. (2011) empirically demonstrated the advantages of inter-agency competition by showing that the period of independent dual enforcement by the FTC and the Department of Justice, when the two agencies competed with each other, generated substantially more antitrust cases per budget dollar than the later, collusive dual enforcement regime that emerged after the 1948 liaison agreement. Their findings echo William Niskanen’s (1971) saying that “competition in a bureaucracy is as important a condition for social efficiency as it is among profit-seeking firms.” (p. 111)

Needless to say, these suggestions do not exhaust the set of potential reforms. Many other possibilities remain open for future consideration.

Concluding remarks

This piece is not to deny the need and the potential value of the new rule, the MSCA. Albeit contestable, it is understandable that, in Japan’s context, the introduction of a complementary regime could be seen as a strategically necessary policy choice, particularly given the persistent under-enforcement of the AMA and the structural causes of that problem, which are unlikely to be resolved in the foreseeable future. (By contrast, the same contextual analysis would suggest that Korea, where concerns relate more to over-enforcement, rather than under-enforcement, has little justification for introducing a similar regulation.)

That said, as emphasised throughout this piece, we should not lose sight of the fact that the key rationale for the MSCA’s enactment lay in the AMA’s persistent ineffectiveness, a problem that remains unresolved. At best, the MSCA is an emergency, symptomatic intervention adopted out of necessity. Its adoption, or even its usefulness, does not detract from the fact that Japan’s policy direction must ultimately lie not in further regulation, but in bolstering competition enforcement under the AMA.

Needless to say, the points discussed here are not exhaustive; they merely sketch a preliminary set of reflections on what stronger AMA enforcement may require. They should be understood as contributing to a broader and continuing conversation—one that must proceed with greater depth and ambition if Japan is to lay the institutional foundations for a more competitive digital and AI economy.

This piece is intended as a small contribution to that ongoing policy debate.

Sangyun Lee is a postdoctoral researcher specializing in competition law and policy, with a keen focus on the intersection of law and public administration. He is currently affiliated with Kyoto University as a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) International Research Fellow.

Check out the SCiDA podcast episode with Sangyun here.