On 5 September 2025, the European Commission issued a landmark decision in Case AT.40670 – Google Adtech, finding Google guilty of abusing its dominant position in online display advertising intermediation in violation of Article 102 TFEU. With a €2.95 billion fine and the Commission’s preliminary view that structural remedies, potentially including divestiture, may be necessary to eliminate Google’s structural conflicts, this decision marks a significant escalation in the enforcement of competition law against vertically integrated digital platforms.

by Anush Ganesh

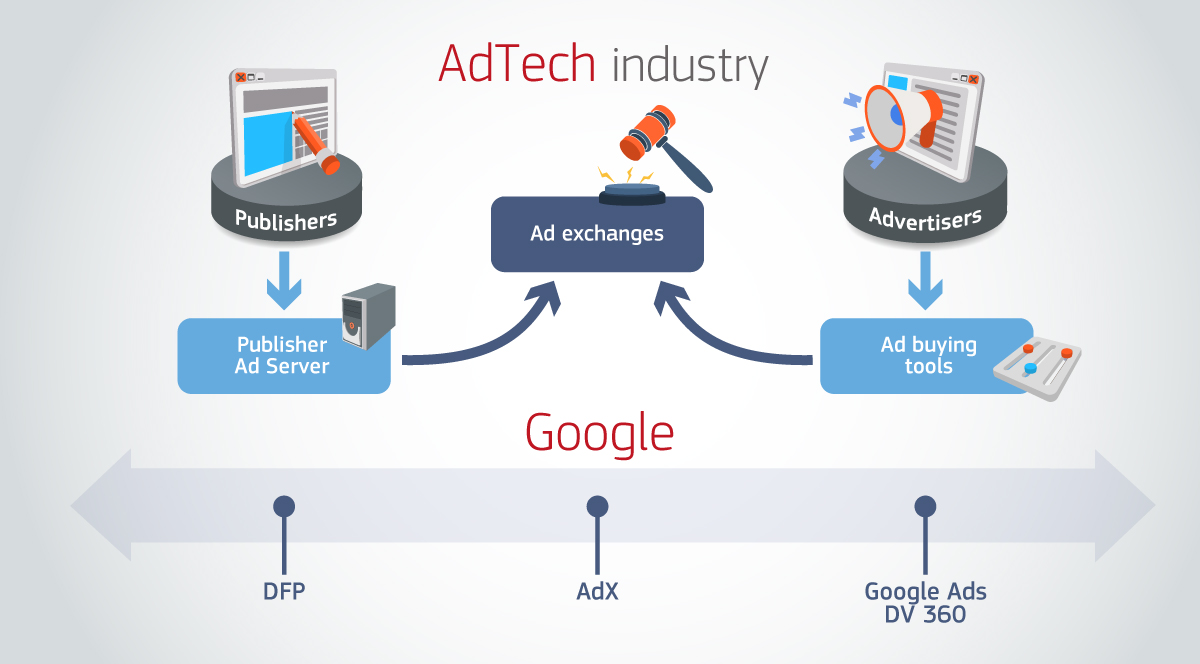

The Decision: A Single and Continuous Infringement

The Commission published the provisional non-confidential version of the decision, a 363-page document, on 16 January 2026. The Commission’s decision begins with a detailed examination of the online display advertising ecosystem (paras 5-309). Google maintains a pervasive presence across the entire advertising technology supply chain, operating tools on both the buy side (Google Ads and Display & Video 360) and the sell side (DoubleClick For Publishers (DFP), now Google Ad Manager) while simultaneously running its own ad exchange (AdX). The decision explains how these different layers of the adtech stack interact: advertisers use demand-side platforms to bid for ad impressions, publishers use ad servers to manage their inventory, and supply-side platforms connect publishers to multiple sources of advertiser demand. Google’s unique position operating tools at every level of this chain sits at the heart of the Commission’s concerns.

Having mapped the market structure, the Commission then establishes Google’s dominance across multiple relevant markets (paras 310-685). Google holds a dominant position in publisher ad servers, where its DoubleClick For Publishers (DFP) commands approximately 90% market share and benefits from significant network effects and switching costs. Google is also dominant in programmatic ad buying tools, where Google Ads and DV360 together account for the majority of advertiser spend. These dominant positions in upstream and downstream markets provided Google with the ability and incentive to favour its own supply-side platform, AdX, over rival SSPs in the adjacent intermediation market.

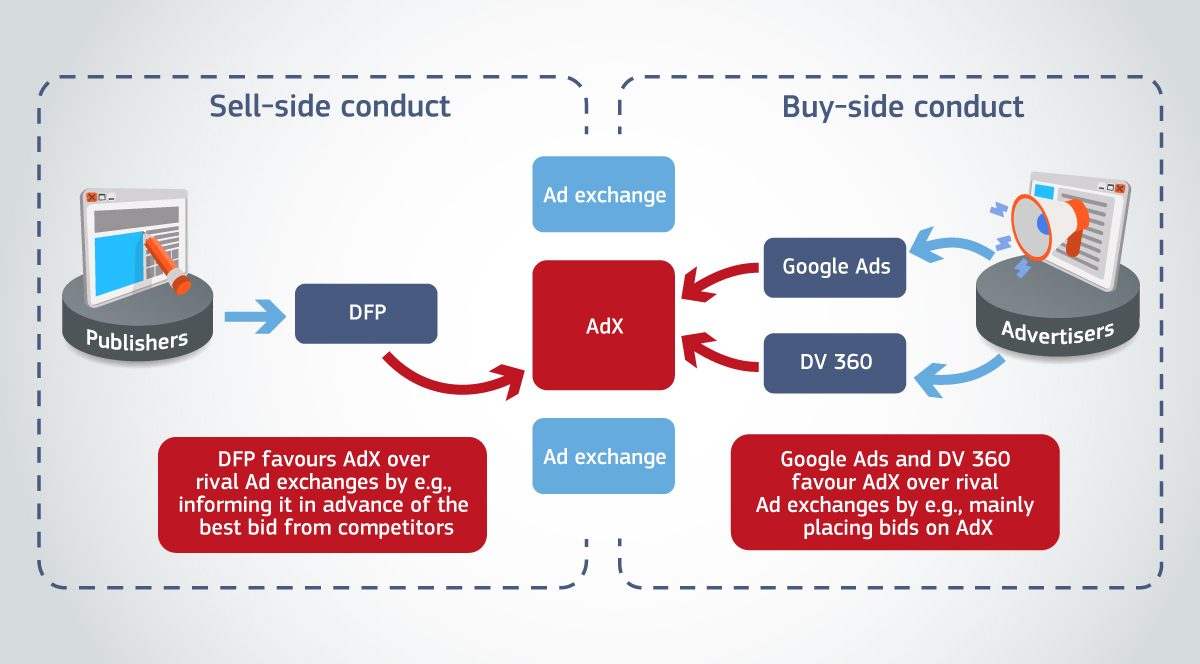

The abuse analysis spans over 1,400 paragraphs (paras 686-2053), reflecting the technical complexity of the conduct and the depth of the Commission’s investigation. The decision identifies two distinct but interconnected abuses:

On the buy-side (paras 718-1225), Google leveraged its dominance in programmatic ad buying tools to favour AdX through three practices: channelling advertiser demand preferentially through AdX, artificially inflating impression values through deliberate second-pricing mechanisms, and placing systematically lower bids on rival SSPs to hinder competing auction technologies.

On the sell-side (paras 1226-1694), Google leveraged its dominant publisher ad server to advantage AdX through practices relating to the traditional waterfall auction system, including the ‘First Look’ and ‘Last Look’ advantages, as well as implementing measures to disadvantage Header Bidding (a technology allowing publishers to solicit bids from multiple exchanges simultaneously) and designing Open Bidding in ways that maintained AdX’s competitive position.

Both abuses share the common objective of favouring AdX over rival SSPs, are interconnected through Google’s vertically integrated structure, and were implemented contemporaneously from January 2014 onwards (paras 2058-2060). The Commission found that each strand of conduct also constitutes an independent infringement of Article 102 in its own right (para 2056), providing a robust legal foundation should any element be successfully challenged on appeal. Notably, the decision addresses ne bis in idem concerns arising from the French Competition Authority’s 2021 decision on related conduct (paras 50-86), concluding that the Commission’s investigation covers distinct practices and effects at the EEA level.

Article 102 Framework: Self-Preferencing and the Google Shopping Legacy

The decision represents the maturation of the self-preferencing doctrine that emerged from Google Shopping and was further developed in Servizio Elettrico Nazionale. The Commission’s legal framework rests on several key propositions that warrant attention from competition law practitioners.

The decision establishes the objective concept of abuse and the distinction between competition on the merits, as envisaged initially in Post Danmark I, and exclusionary conduct (paras 689-691). It confirms that Article 102 applies to leveraging conduct where dominance, abuse, and effects need not be in the same market (para 693). Google’s dominant positions in publisher ad servers and programmatic ad buying tools were leveraged to distort competition in the adjacent market for supply-side platforms, where Google’s AdX faced competition. This articulation of the leveraging doctrine provides clarity for future cases involving vertically integrated platforms operating across multiple markets simultaneously.

On the question of effects, the Commission applies the capability standard established in earlier case law: the conduct must be ‘capable’ of producing exclusionary effects, but actual market foreclosure need not be demonstrated (paras 696-697). While this standard is not novel, the decision provides detailed treatment of how it applies in technically complex markets. The Commission identifies reduced innovation incentives and diminished transparency as forms of competitive harm (paras 703-710), recognising that in digital markets, exclusionary effects extend beyond traditional metrics such as price increases or market share shifts.

Perhaps most significantly for future cases, the decision articulates a three-pronged framework for determining when favouring conduct departs from competition on the merits (paras 711-713 for buy-side conduct; and paras 1226-1229 for sell-side conduct). The framework asks whether the dominant undertaking treated its own services more favourably than rivals, whether competitors could replicate the conduct using their own resources, and whether additional circumstances indicate departure from normal competitive behaviour. Following Google Shopping, the Commission explicitly rejects the application of the Bronner criteria to self-preferencing cases (paras 1077-1079 and 1231-1232). The high threshold for refusal-to-deal cases, which requires demonstrating indispensability of the input, elimination of effective competition, and absence of objective justification, does not apply where a vertically integrated platform discriminates in favour of its own downstream operations. This distinction is crucial: platforms cannot escape scrutiny for self-preferencing conduct simply by arguing they have not refused access entirely.

The Waterfall, Header Bidding, and Google’s Response

Understanding the decision requires some familiarity with how online display advertising auctions operate. When a user visits a webpage, the publisher’s ad server decides which demand sources get the opportunity to bid for the advertising slot and in what order. Given Google’s approximately 90% market share in publisher ad servers, this gatekeeper role is significant.

Under the traditional Waterfall system, the ad server offered impressions to demand sources sequentially rather than simultaneously, working through a ranked list until a buyer was found. The Commission found that Google designed this system to give AdX structural advantages over rival SSPs (paras 1260-1276). Most significantly, AdX enjoyed ‘First Look’ privileges, allowing it to see and respond to competitors’ bids, and ‘Last Look’ advantages, enabling it to match or beat the winning bid from rivals. These informational asymmetries meant that rival SSPs were competing with one hand tied behind their back: AdX could observe the market and respond strategically while competitors bid blind.

Header Bidding emerged around 2015 as the industry’s attempt to level this playing field. The technology allowed publishers to solicit bids from multiple exchanges simultaneously before calling the ad server, creating genuine real-time competition. For rival SSPs, this represented a lifeline while for Google, it represented a threat. The Commission found that Google responded with both technical and economic countermeasures (paras 1277-1328). Through its demand-side platforms, Google adjusted bidding behaviour to make Header Bidding appear less attractive to publishers, effectively penalising those who adopted the competing technology. The Last Look advantage and Dynamic Revenue Share feature allowed AdX to continue diverting impressions away from rival SSPs participating in Header Bidding (paras 1297-1318).

Google also introduced Open Bidding as its own alternative to Header Bidding. While presented as a solution offering similar functionality, the Commission found that Open Bidding was designed to preserve AdX’s competitive advantages rather than create genuine parity (paras 1329-1359). Google restricted participation in Open Bidding, charged rival SSPs a fee that AdX did not have to pay, and prevented vertically integrated SSPs from using demand from their own ad buying tools. The decision additionally examines Google’s Unified Pricing Rules, which prevented publishers from setting different price floors for different demand sources (paras 1319-1328 and 1359).

The Commission concludes that Google infringed Article 102 TFEU by using DFP to favour AdX, based on three circumstances: DFP treated AdX more favourably than rival SSPs; the conduct relied on resources inherent to Google’s dominant position that competitors could not replicate; and Google acted against the interests of DFP and publishers while controlling ad inventory that rivals could not effectively replace (paras 1692-1694).

Structural Remedies: Breaking New Ground

What distinguishes this decision from the Commission’s previous Google cases is the explicit contemplation of structural remedies. While the Commission imposed a €2.95 billion fine, its second-largest antitrust penalty ever, the more significant aspect of the decision is the requirement that Google implement measures to cease its inherent conflicts of interest along the adtech supply chain. The decision contains detailed reasoning on why behavioural remedies alone would be insufficient to address the infringement (paras 2113-2138), grounded in the concept that Google’s vertical integration creates inherent incentives to favour its own services that cannot be adequately monitored or controlled through conduct requirements.

The Commission states in paragraph 2164: Google should implement measures that prevent the recurrence of the Infringement. Such measures should ensure the complete removal of Google’s structural conflicts of interest in the adtech stack and, thus, both its ability and incentive to favour AdX, either via its ad buying tools or via DFP. These measures should also ensure that Google cannot circumvent the remedy by replicating the favouring between its advertiser facing and publisher facing services in the adtech stack via other, equivalent conduct. (para 2164)

The Commission drew parallels to the ENI and RWE gas foreclosure commitment decisions, where divestitures were accepted to address structural conflicts between infrastructure ownership and downstream supply. The decision explicitly notes that divestitures have been imposed or accepted as commitments where behavioural measures would have been insufficient to effectively end the infringement and prevent recurrence (para 2108). Google was given 60 days to propose compliance measures (paras 2163-2165), with the Commission indicating it would first assess these proposals before determining whether to impose a structural remedy under Article 7 of Regulation 1/2003.

What Lies Ahead

The decision raises important questions about the relationship between ex post enforcement under Article 102 and ex ante regulation under the Digital Markets Act. The conduct at issue predates Google’s designation as a gatekeeper under the DMA, and the structural remedies contemplated go beyond what the DMA’s obligations would require. Publishers and adtech rivals who have long argued that conduct remedies cannot address structural market power will be watching closely to see whether the Commission follows through on its preliminary view that divestiture is necessary.

The Commission’s approach also finds parallels across the Atlantic. In April 2025, Judge Leonie Brinkema of the US District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia ruled that Google violated Sherman Act Sections 1 and 2 by monopolising the publisher ad server and ad exchange markets. The remedies phase concluded in November 2025, with the Department of Justice seeking divestiture of AdX, open-sourcing of DFP’s final auction logic, and contingent divestiture of DFP if initial measures prove insufficient to restore competition. Judge Brinkema’s ruling is expected in early 2026. This transatlantic convergence on both liability findings and the inadequacy of behavioural remedies may prove mutually reinforcing, with each jurisdiction’s approach informing the other as both grapple with how to unwind over a decade of self-preferencing conduct.

For competition law more broadly, the decision advances the framework for addressing self-preferencing by vertically integrated platforms. The detailed application of the Google Shopping principles to a complex intermediation market provides guidance for future cases, while the Commission’s willingness to contemplate structural remedies, imposed only twice before in EU antitrust enforcement, signals a more muscular approach to digital markets enforcement. Whether behavioural remedies can ever adequately address the conflicts of interest inherent in vertical integration across digital supply chains remains the central question, and the Commission’s ultimate determination on Google’s compliance proposals will shape enforcement policy for years to come.

The case also highlights the continued relevance of Article 102 alongside the DMA, particularly for conduct that predates designation or for remedial measures that require going beyond the DMA’s prescriptive obligations. As digital markets regulation continues to evolve across jurisdictions, the Google AdTech decision will serve as an important precedent for understanding how traditional competition law tools can address platform power in technically complex markets where the lines between infrastructure provision, intermediation, and downstream competition have become thoroughly blurred.